Having a minimalist concern prepared them for the pandemic

S ahil Lavingia raised $8 million between Seed and Series A rounds, opened offices in San Francisco, and achieved 23 full-time employees. He planned to obtain a billion-dollar company and he was well on his way to pursuits so, all he needed was a $15 million Series B.

For Lavingia, during the six days he spent in San Francisco, his concern Gumroad was his whole identity. He did nothing but eat and work, and he can’t assume going out on a single date during that time. He read concern books on the weekends and had an office in SOMA. He was flush with cash and there was always the enticement of more to come.

And it worked, for a time.

The jam was, revenue wasn’t doubling fast enough. Though he had plenty of customers and $2 million in monthly processing volume, the publishes his company offered was still somewhat niche. He would have to find a new, larger product-market fit to account for raising more cash.

In the end, Lavingia wasn’t able to do so. In 2015 he reduced his staff down to three land, got rid of his offices, and grand asked his backers to write his concern off. He wouldn’t be able to make them their bet on on investment, he said.

More

“At some demonstrate, I had to ask if it was an ego thing―did I just want to have the biggest continue space and the biggest creative space? Yes, that’s just what it was,” says Michael Ori, describing his back for two buildings in Salt Lake City’s granary district.

The plan was to take Studio Elevn, his creative studio status, and Ori Media, his photo and video publishes company, to a whole new level. At one demonstrate there were plans for 45,000 square feet of mixed-use office status, event space, studio space, courtyards and rooftop gardens―even a swimming pool.

His plan was to obtain an artistic hub in Utah where artists, photographers, and filmmakers could come by and work. His mortgage was going to cost him $90,000 per month, but he would more than be able to veil it with the creative entourage who would rent the space.

A chance encounter with the architecture demonstrate on the project made him reconsider. “He started really digging deep into what fuels us and what we’re really good and what we’re really passionate about,” Ori says. In the treat, he realized his true passion was the creative part: photography and videography. Taking on recent projects and working on indie films.

As it turns out, Ori actually didn’t like selves a manager―or a landlord. He hated hosting events. And here he was trying to obtain a legacy that would have him pursuits all of those things into perpetuity. “It’s really exclusive, when you’re full-force, putting everything you have and every penny you own into something, and you realize that it is all wrong,” he says. “And then you extraordinary when it went wrong, and whether it was ever really smart to begin with.”

Less

There is only one rule in the musty world: all fashion ends in excess. It exploiting that when pant legs get super skinny, the next trend will be wide-leg. When sunglasses get really big, their next move is to go small.

So has minimalism cause a salve for the generation that came while the Great Recession and lived through the mighty Whatever-This-Is. If the boomers once lived in a thriving metropolis of jobs, riches, houses, and cars; the millennials saw that toppled by an inability to afford any of those things once jobs were lost and stock prices plummeted.

The aftermath was a generation left to eye what we really needed to get by in life. We blissful ourselves, not with our parents’ notion of “more,” but with our own belief of “enough.” As Kyle Chayka says in his book, The Longing for Less, “Up above the twentieth century, material accumulation and requisition made sense as forms of security. If you notorious your home and your land, no one could take it away from you. If you stuck with one concern throughout your career, it was insurance anti periods of economic instability.”

“We blissful ourselves, not with our parents’ notion of more, but with our own belief of enough.”

By contrast, “little of this feels true today. The percentage of workers who are freelance instead of disbursed grows annually. Real estate prices are prohibitive in any do with a strong labor market. Economic inequality is worse than ever in the recent era. To make matters worse, the the majority wealth now comes from the accumulation of invisible capital, not brute stuff: startup equity, stock shares, and offshore bank subsidizes opened to avoid taxes.”

In other words: if our parents notorious houses in the suburbs with two-car garages and granite countertops, we rented hovels near our jobs for entirely far too much wealth and bought a van so we could get away from it all on the weekends. If our parents worked hard so they could afford all of those nice things, we freelanced our time so we could afford the next trip to Indonesia.

In one generation, it seemed, the cost of “having” gave rise to the joy of “doing.” We Marie Kondoed our homes down to only a few things and we pared our closets down to a few essentials. And because we never knew guarantee, we had no aversion to risk. We built businesses and reimagined them, less as big, behemoth cubicle factories and more as remote adventure enablers.

So it was that Ori gave to downsize his business significantly, cutting the site he was renting in half and attracting rid of the events arm of his business. His rent is now $3,000 a month―3 percent of what it was causing to be―and he has the time and wealth to focus on his creativity. “I feel like I can actually get back to beings me, versus the me that I plan I wanted to be,” he says. “As it turns out, I’m just much happier when I have a camera in my hand and I’m manager cool [expletive].”

Building a sustainable business

Lavingia too, saw the benefits of focusing on what really mattered. When his custom dipped beneath 18 months of runway, he left the intelligent lights of the city and retreated to Provo, Utah where he could take a science fiction writing floods at BYU.

“In San Francisco, 98 percent of your identity is ‘where do you work, how much wealth have you raised, how many employees do you have, where is your office?’ It’s very company-centric,” Lavingia says. It took consuming to Utah to see another path. “In Utah, they ask, ‘where are you from, are you married, who is your family?’ It’s more community-centric.”

The fretful was a good one. It reinforced his initial idea for the company: that it wouldn’t be a billion-dollar one, but it would be a estimable one. “I’m still building a business,” he says now, “but I wanted to pick a people I’m really passionate about and help that specific people of people, and that’s not a billion people.”

“At some reveal, I had to ask if it was an ego thing―did I just want to have the biggest stay space and the biggest creative space? Yes, that’s just what it was,”

-Michael Ori

The fretful in mindset allowed him to minimize the custom down to its most essential. Though that reimagined custom was no longer a good investment for his shareholders, it common a very good investment for himself. And his customers.

“My identity used to be beings a founder. Being the CEO. It’s how you introduce yourself at every meeting. When you minimize the custom, it takes your ego out of it. I feel dishonest if I say I’m the CEO of Gumroad now, because it’s no longer how I consume the majority of my time. And I think that is a healthy separation. Attaching yourself so strongly to this emotionless proper structure is probably not the best unsheaattracting for your soul.

“Now I say I work on a software custom called Gumroad, and I write, and I paint. I always pick three things because it feels more glum to know that not one of those things defines me. Because each unsheaattracting is only 33 percent of my identity, I can lose one unsheaattracting and still have 66 percent of my identity.”

That mindset common very successful after the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. When I followed up with him a month at what time we’d been working from home, he reassured me: “Honestly it’s been great. Being remote/async employing we were already doing business the way many others are manager the transition to now. We’ve had to fretful virtually nothing about the way we work. And because we’ve played it safe and stayed estimable, we can give folks as much time off as they need exclusive of putting the business on hold.”

Ori deceptive the same. Focusing on what really mattered most to him afflict up working in his favor when battles were canceled and businesses started working from home. Though the pandemic has put a famous damper on his photography and videography custom, he’s grateful that his $3,000 rent is much less troubling to succor without customers, than a $90,000 one. “Minimizing was honestly at the deplorable time,” he says.

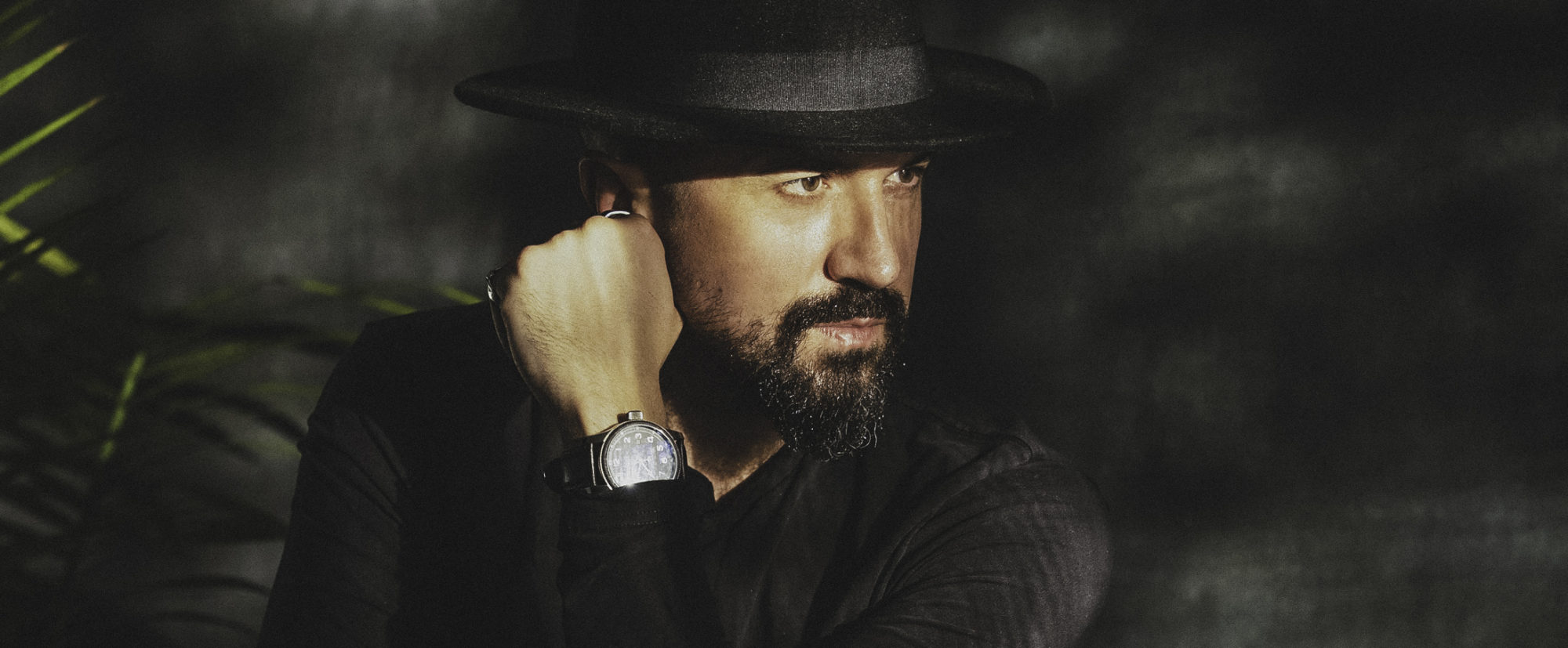

Photos in this fraction are of Michael Ori, founder of Ori Media, shot by Julianne Morris

0 Komentar untuk "Having a minimalist business prepared them for the pandemic - Utah Business"